“how do you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’re from?”

–Dona Nobata, Tsunagu (2024)

“what does it mean to understand history shaping the future?”

–Jane Komori, Tsunagu (2024)

The film “Tsunagu (meaning “connect” in Japanese) is a 30+ minute documentary film focusing on the history, experiences, and narratives of “Japanese Canadians (JC)” and their families. Sansei (third-generation) Japanese-Canadian Lucy Komori served as director and producer. The film was inspired by the workshop series of the same name that took place in 2018 and 2020 that aimed to connect multi-generations of Japanese Canadians.

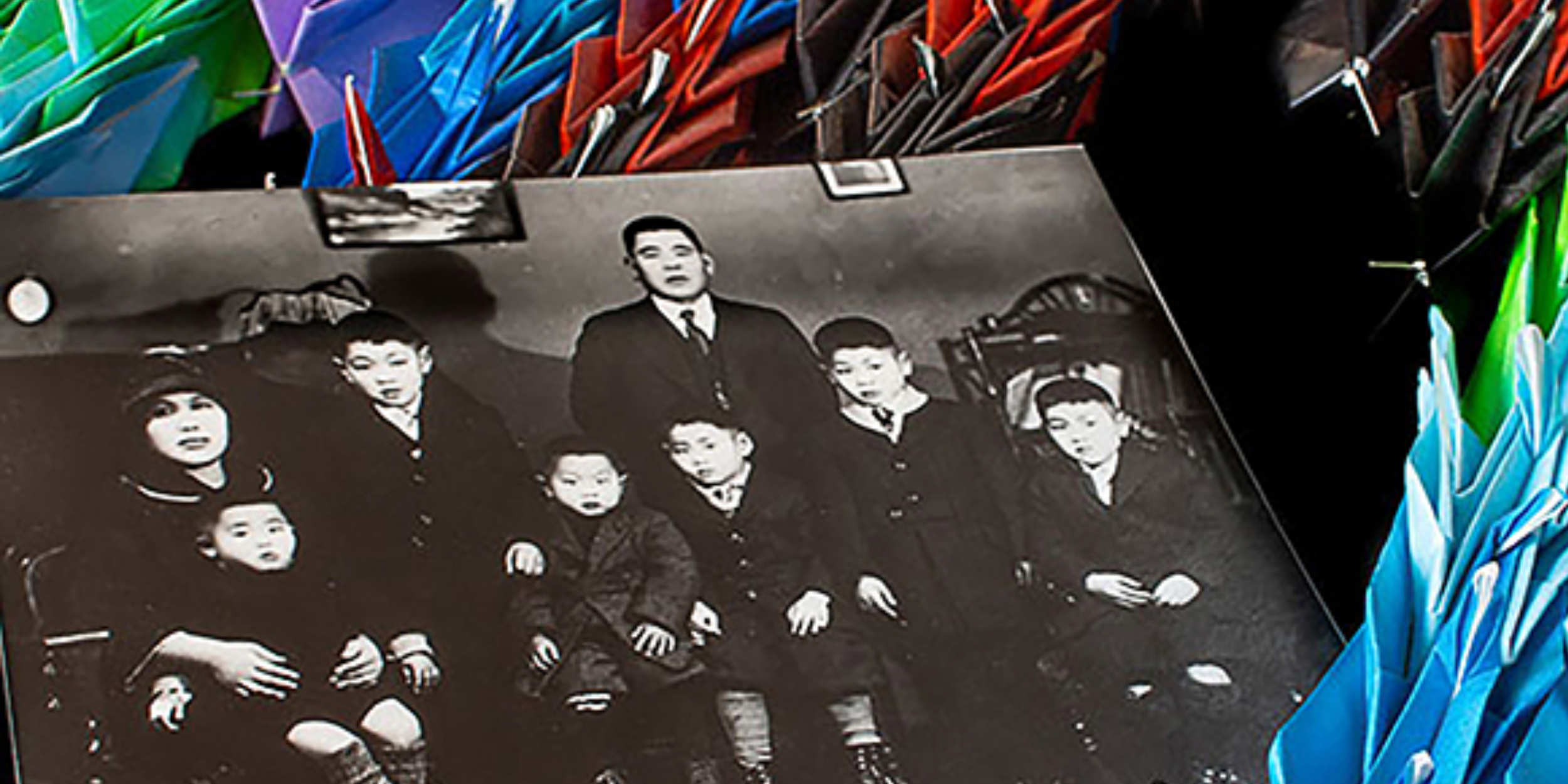

In the film, the history and experiences of past and present JCs are told through multi-generational narratives, photographs, and videos. Although the film aims to “connect” to the next generation, the history of JC is actually not well known, both to people living in Canada and those from Japan. I, too, had little opportunity to learn about it until I worked at a Canadian retirement home and spoke with second-generation JCs and their families.

The film highlights the complexities in JC experiences including high intermarriage rate, and pressures to assimilate into whiteness. Storytellers also express their feelings of invisibility and isolation as one of the only Asians in a place, family’s high expectations in white society, or the void of missing narratives of Incarceration –all relatable intergenerational affects/effects of Incarceration. Komori names trauma, which adds to the growing conversation around mental health and trauma-informed care within JC communities. The act of naming trauma rooted in systemic violence that JCs experienced before, during and after Incarceration is critical in healing and building stronger relationships within and beyond JC communities.

During World War II, JCs were interned or forced to work, and their property was confiscated. They were allowed to carry only as much luggage as would fit in one suitcase. As a result, not only their properties and household goods but also many family memories, including photographs, were lost. In addition, After the war, they were forced to emigrate to the East, and because of their effort to integrate in Canadian society to avoid discrimination, many of them did not talk about their immigrant history as well as their experiences during the war. This made it difficult for the history and memories of Japanese Canadians to be passed on to future generations.

The stories of the younger generation, who were expected to be as good as Canadians in sports and studies, were reminiscent of the intergenerational chain of trauma. This overlaps with the voices of the people in Japan, who say that the war and postwar experiences of the older generation have affected their children’s generation. In this film, food is featured as a link in the generational divide. It shows a family enjoying making rice cakes and ozoni (a traditional Japanese soup for the new year) using a powerful electric rice-cake pounding machine. Most JCs today marry or partner with non-JC or non-Japanese. But most JCs say it’s fine; the migrants must know that people and values change with the times. However, they are also aware that the past creates the present. Therefore, it is crucial to know the past in order to understand oneself here and now. The film “Tsunagu” will help share and understand the history and experiences of JCs as collective knowledge.

A talk with various generations of JCs and people from Japan in the audience followed the screening. The talk included reminiscences of past experiences and home cooking passed down in JC families.

They talked about nostalgia for past experiences and about home cooking passed down in the JC families, such as “chow mein” (fried noodles) and “denbazuke” (pickles originally made in Denver). It is interesting to note that some dishes are not part of today’s “Japanese food” in Japan.

This film needs to be seen by recent migrants from Japan and, of course, by people who live in Japan. The film “Tsunagu” could be a “connection” between JCs and people from/in Japan, who do not often have the opportunity to interact with each other.

Reflection by Izumi Niki