“how do you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’re from?”

–Dona Nobata, Tsunagu (2024)

“what does it mean to understand history shaping the future?”

–Jane Komori, Tsunagu (2024)

Tsunagu is a film that follows the stories of five Japanese Canadians (JC) sharing their family stories and the present-day impressions left from the memories of Incarceration and wartime measures. Director Lucy Komori has been hosting events (sharing the film’s name) that facilitate multigenerational conversations amongst nisei, sansei, yonsei and gosei JCs since 2018. Through these discussions, Komori found that everyone was eager to talk and fill gaps in family history, especially younger JCs. The film invites audiences of all generations to be curious and ask questions about family histories. The filmmaker’s yearning for JC family and community stories is evident.

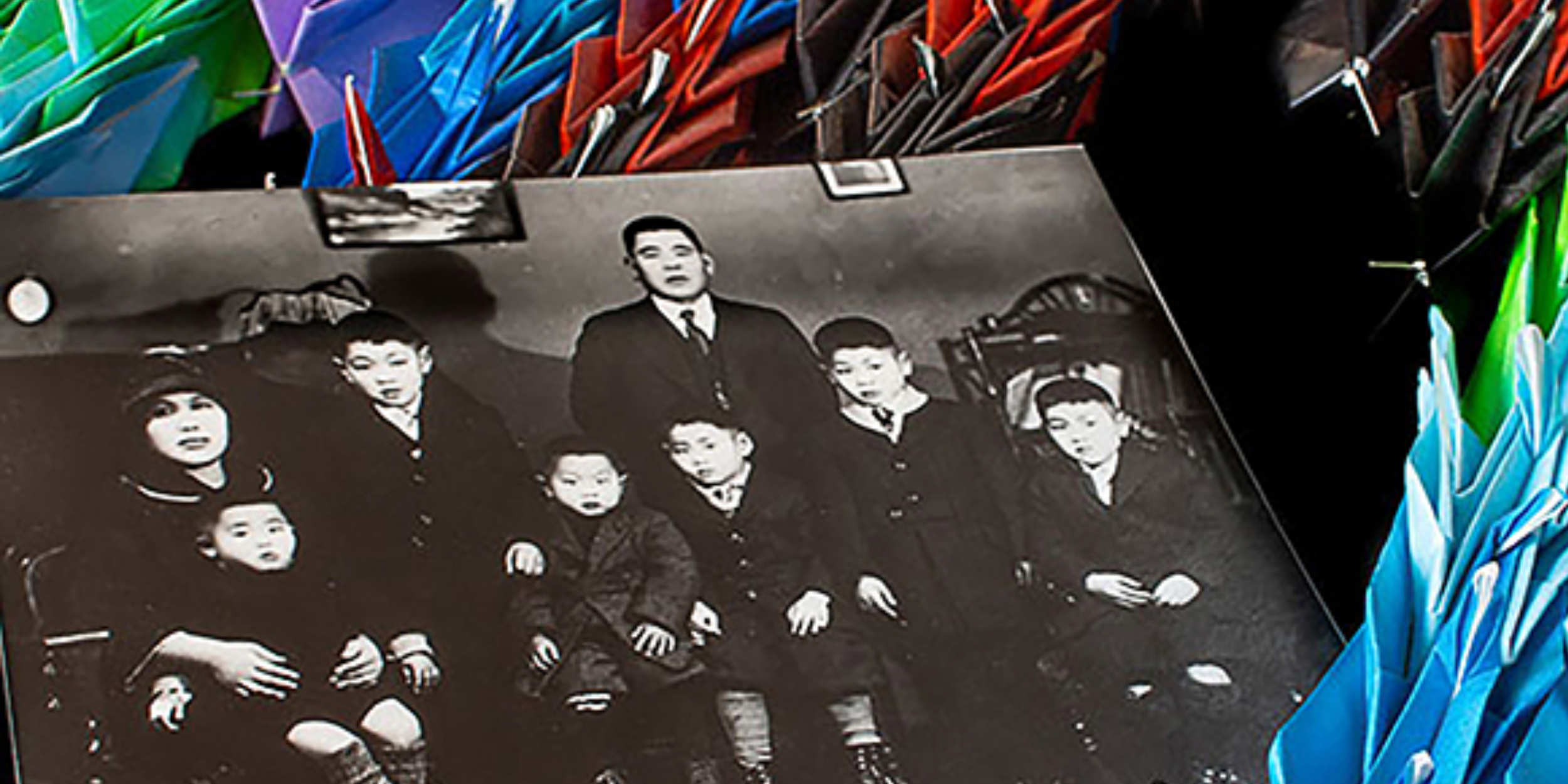

It hits home when multimedia artist Dona Nabata remarks “now there’s no one to ask” when reflecting on her family history. As I reflect on my family histories, those who can share the stories with me have either passed too soon, or their memories are fading from dementia. I grieve the first-person narratives of my extended family’s histories to this land we call Canada; yet as photographs and heirlooms are shared with me, I can feel that these stories are still alive. In the film, Nabata’s question “how do you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’re from?” invites reflection, giving the audience permission to look back to move forward. This set the tone for the rest of the visual journey. The film interlaces the narratives of being nisei, sansei or yonsei by placing them in conversation with one another. Through interviews with the storytellers as well as photographs and family home videos, the film weaves together four interconnected threads: Family History, Impact of Family Trauma, Tradition Passed Along, and Identity.

The film highlights the complexities in JC experiences including high intermarriage rate, and pressures to assimilate into whiteness. Storytellers also express their feelings of invisibility and isolation as one of the only Asians in a place, family’s high expectations in white society, or the void of missing narratives of Incarceration –all relatable intergenerational affects/effects of Incarceration. Komori names trauma, which adds to the growing conversation around mental health and trauma-informed care within JC communities. The act of naming trauma rooted in systemic violence that JCs experienced before, during and after Incarceration is critical in healing and building stronger relationships within and beyond JC communities.

Throughout the film, Komori draws from the power of storytelling –the filmmaker depicts stories and memories as family and community inheritances. Inheritances such as photographs, gustatory memories like food/recipes, spiritual practices, gardening, and commitment to social justice function as pieces of ancestors’ legacies that the storytellers carry with them.

The film closes with clips from Powell Street Festival. The Yonsei storytellers express that many younger JCs are participating as the festival itself is adapting to the present. Jane Komori, a Yonsei storyteller asks, “what does it mean to understand history shaping the future?”

The film seems deeply personal to the filmmaker; Komori’s tribute to her family which extends to JC communities and beautifully capturing the deep connections that bind them together. The intimacies of family and community intertwine through the narratives. Themes of loss and by extension, the grief of lost narratives/irretrievable memories evoke a longing to unearth family stories and carrying them forward.

The moving narrative pulled me towards the power of storytelling and a slight sense of forgiveness to the existing gaps in my family memories. I piece together –tsunagu– fragments of photographs and stories I have already been told. I grasp for moments that might help shape the untold stories and connect me to the family members I never had the chance to meet.

Reflection by Ai Yamamoto